PARADIGM SHIFT: A REVIEW OF RALIAT IBRAHIM’S THE TWENTY FIRST GIFT

Book: The Twenty First Gift

Author: Raliat Ibrahim

Reviewer: Mahfouz A. Adedimeji, Ph.D.

Pages: 84

As the whole world continues to mourn the demise of the father of modern African literature, acclaimed literary artist, master writer and quintessential novelist, Prof. Albert Chinualumugu Achebe, it is gratifying and comforting that a person like Achebe did not die in vain as he had sired many worthy literary children. It is also a welcome paradigm shift that fiction writing has transcended the boundaries of its largely patriarchal foundations and women writers are now holding sway. From the trail-blazing oldies like from Flora Nwapa, Mabel Segun, Buchi Emecheta, Tessy Nweme and Zainab Alkali, we have a growing list of newbies such as Sefi Atta, Nkachi Adimora-Ezeigbo, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and now Raliat Ibrahim, l who has made a strong statement with her debut The Twenty First Gift.

Rooted in the Aristotelian conception of literature as the imitation of reality and the Horacian perception of art as that which edifies and delights along with sapientia (high morals), Raliat Ibrahim’s debut novella strikes one as a deeply engaging story that thematises the concept of life being reciprocal. In other words, it is what we give life that life gives back to us, an amplification of the Qur’anic affirmation, “Whoever does good does so to his own benefit; and whoever does evil, will suffer its evil consequence. Your Lord does no wrong to His servants” (Q41:46). Apart from the double entendre of the title, The Twenty First Gift, which means the last of the 21 gifts as well as the gift presented on the 21st birthday, a reader of the riveting love story is spell-bound by the racy prose, quick-paced story-line, episodic structure, suspense-surprise strategy, and the profound literary artistry underpinning the totality of the aesthetics that gives the novella both class and panache.

Synoptically, the story centres on Atana, an orphan pushed out to work by her uncle and wife, who cannot contemplate having a sixteen-year old girl as a “burden” on the family. The quest to avoid the daily insults, after fruitless searches, eventually leads her to the gate of a single, rich, young Civil Engineer, Fasna Tona, who employs the girl with a good pay and assists her in realising her educational goals while nursing a secret admiration. Fasna handles his hidden love with uncommon restraint, especially in the context of the 21st century when everything is on the fast lane. This is because even when the protagonist has to move into Fasna’s house when her good-natured uncle (Lera) and cantankerous wife (Ima) insist on Atona’s marriage to a village carpenter rather than having a university education, and accuses her falsely of being pregnant thereby putting her on the lowest emotional ebb, Fasna does not take advantage of her. Through the moral and financial support of Fasna, at twenty-one, the brilliant Atana is already an undergraduate of the Federal University of Medicine, the appropriate age Fasna deems it fit to present his heart as the twenty-first birthday gift to her on campus. However, life is not that smooth as the rambunctious Enan appears on the scene, creating conflict and twists with deadly consequences.

Enan Afutna is characterised by Raliat as a bitter person, whose resentment began in “his mother’s womb” (p.24), a product of an unwanted pregnancy. Enan’s mother, Asunana, overcomes the disappointment and marries Agin, who also takes Enan as his own child. At tender age, though brilliant, Enan starts to manifest traits of what will characterise his troubled life by breaking a classmate’s finger at age five and using a knife at seven, after being insulted as a bastard. At sixteen, he has graduated to indulgence in alcohol and smoking while at the same time crowning his violence with murdering his step-father. It is this devious character that now loves our admirable Atana when we meet him again as an undergraduate at the Federal University of Medicine! Enan is so jealous that another course-mate, Zom, who is just an ordinary friend, is almost killed when Enan stabs him at the neck region for the criminal offence of talking to Atana! So, by the time Enan knows of Atana’s relationship with Fasna, hell is let loose: there is a gun attack that would have brought Fasna to his end if not for his bullet-proof car and there is a bomb attack later on his company, a development that is first reported to have taken his life along with 24 others, leaving Atana in deep sorrow.

It ultimately turns out that Fasna did not die; his goodness to an already bribed company security officer who spilled the beans at the eleventh hour saved his life, but not the lives of others. At the end, it is an irony of fate that the same runaway father, who impregnated Enan’s mother before going abroad for further studies, also fathered Fasna. Enan confesses he loves Atana and lives for her, but cannot afford to let her be sorrowful, realising her heart is with Fasna. Enan tells Fasna in Atana’s presence before he shoots himself in the head: “It was stupid of me to have thought of killing you. I was hoping one day she would love me but now I see you’re probably the only one for her. All that matters to me is for Atana to be happy. My presence here would disturb things” (p.83). The tragic ending is ameliorated by our novelist through a short epilogue by which means we gladly know of Atana’s second pregnancy four years later.

Without doubt, Raliat Ibrahim’s The Twenty First Gift is a game changer, a paradigm shift, in contemporary fiction writing as well as a thrilling reading experience. It is remarkable that the powerful love story is told in 84 pages which makes the novelist a good upholder of the principle of economy, which Ebele Eko in her Effective Writing (1999, p.1) refers to as “the first quality of any good writing”. In other words, Raliat Ibrahim does not waste the reader’s time with boring details, superfluous plots and irrelevant information, a good strategy of encouraging the young to re-embrace the culture of real reading instead of the pervasive culture of reading through texting, tweeting, pinging and Facebooking.

The moral of the story is also compelling that if you are responsible, good-behaved and hard working, it becomes a fait accompli to achieve your goal as vividly evident in Atana, a counterforce to the character of Enan who loses all: his love and life. The novel(la) is a clarion call to the youth, especially at their adolescent years, to prioritise right things and pursue what is good and noble as everyone will ultimately get what they deserve – just as the kind, patient and good-natured Fasna also receives the gift of Atana’s love.

Despite the overwhelming strengths of this novel which make it merit every minute any reader spends on it, it must be admitted that it is not perfect – no one is actually perfect despite Enan’s remarks, “You are perfect, Atana” (p.82). Critically, apart from the mechanical infelicities that dot the body of the beautifully packaged book (this is a book you can judge by its cover), it is curious that the physical setting of where the events take place is omitted. We can only make an educated guess, given the unresolved crimes by the police and the use of a bullet-proof car by a private citizen, which is suggestive of insecurity, that the setting is a Nigerian city, most likely a state capital, with the full paraphernalia of the “Government Reserved Area” (GRA).

While the use of Improvised Electronic Device (IED) is further emblematic of the Nigerian setting of today in a way, its application appears implausible (like having sunset at 9:00p.m. in Nigeria) and exaggerated (like killing a mosquito with a harmer) when you bomb a company to make even with a rival-lover, killing 24 persons in tow. I think there are other ways of eliminating a rival without making a statement that is characteristic of Boko Haram, MEND and such other deviant groups that hold Nigeria to ransom. Numbering the chapters serially, it is agreeably unnecessary to name them, would also make the book better organised and easier for reference in the highly recommended second edition, which is also expected to contain the missing bibliographical details of the current edition.

Ultimately, Raliat Ibrahim’s The Twenty First Gift is an unputdownable story that deserves serious attention and establishes itself as a timely addition to the unfolding literary efflorescence in Nigeria. Raliat certainly does a marvelous job by weaving together a series of plots to resolve a major conflict, while artistically deploying the elements of suspense, surprise, flashback, catharsis and deu ex machina (the machine God; the type that brought Fasna back to life after his announced death) with other elements of prose to drive home her message. While thematising that life is reciprocal, a give-and-take phenomenon, it also teaches the lessons of love, determination, optimism, patience with the subtle message that violence will always consume the violent one way or another.

The Twenty First Gift is a gift that every teenager will primarily benefit from, including undergraduate students in their twenties apart from the general readers. It certainly belongs to the class of those few books “to be chewed and digested”, not those “to be tasted (or) to be swallowed” as Francis Bacon wrote in 1597. Everyone should therefore get a copy and digest it for his/her own edification and delight as Horace is earlier indicated to have contended. The Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA), Kwara State Chapter, may also consider the benefit of including the title among those to be read by secondary school students in the second ANA/ Yusuf Ali Reading Campaign project, on its merit, not just because the book is dedicated to the eminent legal practitioner and promoter of arts and literature himself, the esteemed Mallam Yusuf O. Ali, SAN.

Reference

Eko, E. E. (1999). Effective writing. (Revised edition). Ibadan: Heinemann Educational Books (Nig.)

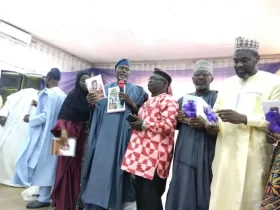

Dr. Adedimeji presented this review on March 29, 2013 at the Banquet Hall of Radio Kwara, Ilorin.

Leave a Reply